“… many tales were circulated about his magical inventions, I came to think of him as a sure-enough ‘wizard’, superhuman and unapproachable. I had listened to his wonderful ‘talking machine’ and heard of his incandescent electric lamp, so when one time a very bright evening star appeared in the direction of the Edison Laboratory I was quite ready to believe the story that it was a new Edison invention, a huge electric star”

“Now the ‘wizard’ of my boyhood became an intensely interesting human being, humble, friendly, and quite approachable.”

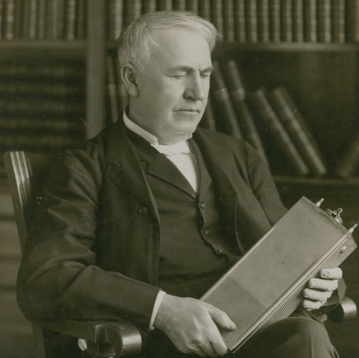

Walter Elam Holland first reported directly to Thomas Edison in 1904. In the 1965 self-published book, “Reflections”, Walter wrote that Edison, the wizard of his youth, worked 16 to 18 hours a day, “taking only a half-hour nap on a table or desk once or twice.” [p.16]

Walter Elam Holland was my great-grandfather’s first cousin. Walter and I share a great-great-great grandfather. My mother first told me about the book “Reflections” when I was eleven or twelve, after I asked if any of our family was a part of history. She told me the book was about his time working in Thomas Edison’s Laboratory.

In fact, as a ‘duobiography’, authored jointly by Alice and Walter Holland, running only 80 pages, the book was written for their children and grandchildren to share both their stories. My grandmother and mother considered the book a family heirloom, documenting a connection to an American legend. Reading it now, I think it’s also a reminder of how our life stories can continue teaching and guiding others long after our lives are over – and in ways we may not have expected.

SURVIVING EDISON

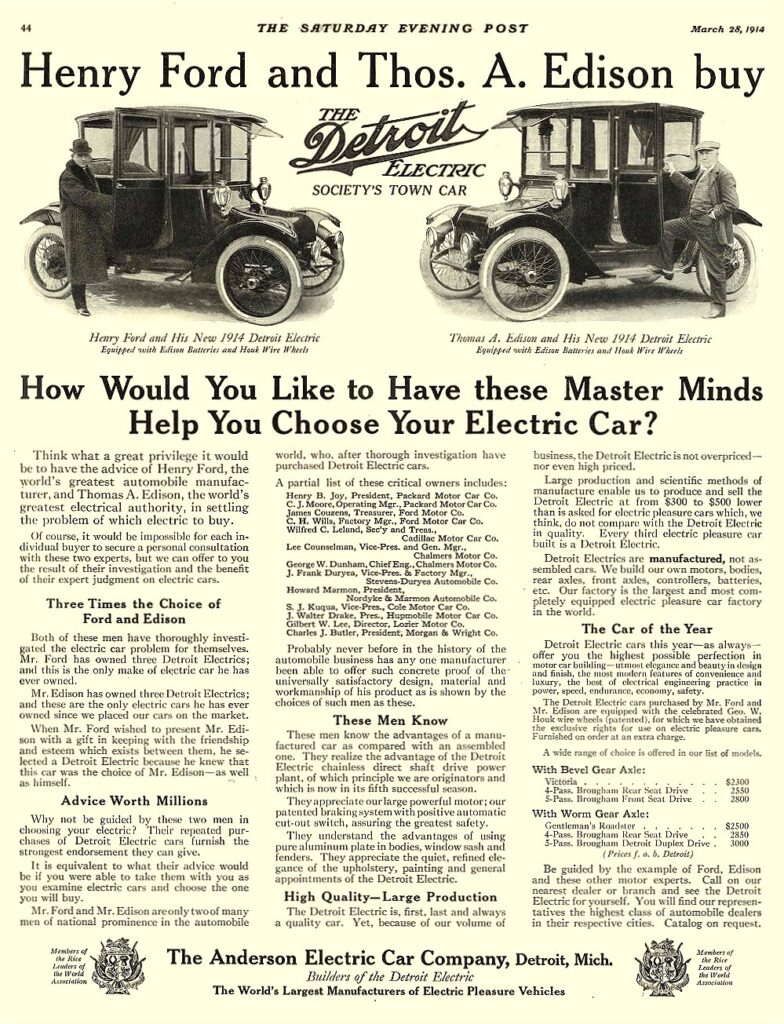

The Battery Experimental Department at the Edison Laboratory in Orange, New Jersey ran 24 hours a day. Three shifts of researchers worked to find and correct problems with the original Edison storage battery. These were the batteries that ran the electric vehicles Edison had been working to develop with his good friend, Henry Ford.

Walter wrote, “Road tests in electric vehicles, as well as laboratory tests, showed that the original Edison storage battery did not have the long service life it was supposed to have”. [p.8] The stakes were high for Edison. Factories were shutting down.

As the researchers worked late into the night, Mrs. Edison would send a midnight supper basket for Mr. Edison, which he would share with Walter and other men in the lab. Around 12:30am, the lighting would dim to darkness for 30 seconds as the electrical plants switched over. When this happened, “Edison would fold his hands, compose himself as if he were in sound sleep, and when the lights were full again would apparently wake up, with the remark, ‘Well boys, we’ve had a fine rest; now let’s pitch into work again.’” [p.17] Walter considered this a prime example of Edison’s marvelous wit.

Knowing what I do now about Edison’s love for Vin Mariani, a wine mixed with cocaine that he claimed help him stay awake longer, I have a distinctly different view of Walter’s boss. My heart opened up for this distant cousin, trying to keep up. “As Mr. Edison’s assistant in charge of this work, I felt I must be on the job every day as long as he was, that is, 16 to 18 hours a day; but as I didn’t know when he was taking a nap I had to stay awake the full time, in case he wanted to drop in and discuss something.” [p.19]

Working at Edison’s lab had been Walter’s childhood dream. As a kid, he lived near Edison’s West Orange Laboratory in New Jersey, “where many tales were circulated about his magical inventions, I came to think of him as a sure-enough ‘wizard’, superhuman and unapproachable. I had listened to his wonderful ‘talking machine’ and heard of his incandescent electric lamp, so when one time a very bright evening star appeared in the direction of the Edison Laboratory I was quite ready to believe the story that it was a new Edison invention, a huge electric star.” [p.15]

Walter started working at Edison’s company straight out of high school when, “at 18, I had to forego college and go to work.” [p.15] It seems Walter’s lack of education endeared him to Thomas Edison, whose experience with college graduates, according to Walter, “had not been good. The trouble with them, he said, was they had a superior air and thought they knew all there was so they stopped studying.” [p.33]

A graduate electrical engineer by the name of Hooper ran the small-cell lab. He was a college graduate, and he was “strong on theory” as opposed to Edison’s “empirical, cut-and-try method.” Edison told Walter he thought “inventors who depend on theories miss a great deal.” [p.33] He also thought they were too slow.

Walter saw a series of letters Edison sent to Hooper, mocking him for his slowness in getting things done. He addressed the letters, in succession, to “Rev Marcus Aurelius Hooper LLD, Genl Josephus Augustus Hooper, General Hydrochloride Hooper esq., and Prof Hooper. Needless to say, Mr. Hooper felt abused and left shortly after Edison’s return. I was then put in full charge of both battery laboratories and given a raise in salary.” [p.34]

During his time with Edison, Walter tested batteries at an Ontario cobalt mine in -45 degree weather [p.26], fended off “nosey questions” about submarine batteries from a German spy named Kammerhof [p.44], and at Edison’s personal request [p.38], sent a pack of 50 cigarettes to Henry Ford’s son, Edsel, on his 21st birthday.

The cigarettes were another of Edison’s “pranks”. When Walter wrote Edison, requesting a reimbursement of $1.75, Edison replied, “Thank you very much for sending the cigarets and the card. Edsel doesn’t smoke and probably would be disinherited if he tried a cigaret so they were in the nature of a kid. He tried a pipe in Florida and it pretty nearly made him sick and no tobacco enthusiast.” [p.39] Walter considered this another example of Edison’s “very keen sense of humor”.

Walter finally left Edison to work for the Anderson Electric Car Company in January 1913. He considered his time with Edison a “wonderful, rewarding experience”. In his resignation letter he wrote to Edison that he felt “as though I belong to you and the battery. However, a fellow has to look out for himself, and I know you will think none the less of me for taking this step.” [p.47]

Walter and his wife, Alice, took turns writing chapters in their book, “Reflections”. After Walter’s chapter about his time with Edison, Alice wrote that during the summer of 1912, “the strain and stress which Walter had endured in the long grueling drive to find and correct the faults in the original Edison battery caught up with him and he had a nervous breakdown.” [p.13]

ELECTRIC WHEEL OF FORTUNE

After leaving Edison, Alice and Walter rode the roller coaster of electric vehicle development. The Anderson Electric Car Company, manufacturer of “Detroit Electrics”, did not turn out to be the promising industry Walter hoped.

After Walter designed an electric truck, the uncertain market brought U.S. production to an end. Briefly, Australia showed interest in electric vehicles. Walter took off on a sales junket to New Zealand and Australia, shipping two Detroit Electric pleasure cars and his electric truck and himself to meet with Sydney city officials.

It was early 1915, and Walter ran into Henry Ford on the trip. Walter described Ford as “slim and springy, like his Model T car. His attitude is: all things are possible. He carried a beautiful platinum watch, the thinnest I have ever seen. I think he pulled it out as a hint that it was time for us to leave.” Before leaving, though, Henry showed Walter his “experimental room – sort of a museum. We saw the first car he ever built and a ‘cycle car’ (not electric) he was testing.” [p.50]

Although he was successful at selling the vehicles, Walter found a new job on the trip. He returned to Detroit with a canvas bag of Australian gold sovereigns. He delivered the gold and his resignation at the same time.

More promising than Anderson Electric was a new electric vehicle agency he heard about from a friend in Seattle. He took a position as secretary-treasurer of the new company. Walter and Alice moved to Seattle, renting a house “beyond the city limits near Lake Washington and a virgin evergreen forest.” Within three months, the company failed.

Alice and Walter used up all their savings and ended up feeding their kids onions and potatoes from the small garden at the rental house, and “mushrooms gathered by Walter in a nearby field”. When Walter borrowed on his life insurance to get the family to Berkeley, California to stay with Alice’s sister, Alice admitted “we felt very sad about leaving that wonderful country with its magnificent mountains, tall evergreen trees, its lakes and Puget Sound.” [p.54]

Despite finding a stable job – including an office and secretary – with the Walker Electric Truck Company in San Francisco, Walter still wasn’t happy. “His heart was still with research and engineering.” [p.55]

Alice wrote the chapters about the hard times, the unfortunate events. She’s the one who let me know they had kids, had family, had a life beyond the work. Walter didn’t write anything about his kids. Or his own breakdown.

Walter wrote the chapter on Edison, and the one about what came after San Francisco. He found a job he wanted as Research Engineer of the Philadelphia Storage Battery Company where he focused on improving a car starting battery. Although his career started with a promise of electric vehicles, by 1917 the invention of a practical electric starter “made the gasoline car so easy to start and operate that the ultimate doom of electric vehicles was in sight.” [p.59]

RADIOTRON DAYS

With the decline of the electric car, a new, exciting engineering challenge entered Walter’s life. “In 1920 the first radio broadcasting started from station KDKA, Pittsburgh… and it looked as though a new industry was at hand.” [p.61] Philco, what the Philadelphia Storage Battery Company was eventually called, began research and development of home radio receivers.

By 1930, Walter and his team “pioneered with automatic volume control and tone control.” Philco’s “Baby Grand” radio “sold like hotcakes”. [p.63] Then, Philco began producing “Transitone” radios for automobile after-market installation. Walter was promoted to Chief Engineer of Philco following his radio success.

When the Radio Manufacturer’s Association formed, Walter was named chairman of the standardization committee. “One of the early discussions was what to call a ‘radio receiving set’ or ‘radio receiver’. I suggested calling it a ‘radio’ and that was adopted.” [p.64]

By 1929, “television was in the air.” Philco had a partnership with RCA, but RCA was keeping its television research under wrap. Walter took Alice on a trip to San Francisco to meet Philo Farnsworth, the television inventor and developer.

The British Government Television Committee visited Philco in Philadelphia in early 1935. Walter is fourth from the left, in the light colored jacket.

From The Philco Library

Farnsworth moved to Philadelphia and brought his television laboratory to Philco, but it wasn’t a long stay. Walter described Farnsworth as “a brilliant chap, but an egotist who didn’t like suggestions or taking orders. Now and then he would have a ‘brainstorm’ – a new idea not connected to television, and he would follow it up to the detriment of his television work. After a couple of years we had to let him go.” [p.66]

While television didn’t pan out for Walter, his radio work led him to be appointed as “liaison to the composer Leopold Stokowski. ” Philco sponsored the broadcast of the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Stokowoski. The composer wasn’t happy with the quality of broadcast sound and was interested in how it could be improved.

Walter described Stokowski as an “apt pupil” in broadcasting and radio. They worked together for several years, often meeting for business dinners and at the composer’s apartment. One evening, Stokowski let Walter and Alice sit in his box seat with friends.

On another evening, the last concert of the season, Walter wrote, “Stokowski sent word he would like to see me. It was a warm spring night. I waited in the wings off-stage while he spoke with several people who wanted to say good-by. He then led me to his dressing room in the very top of the Academy of Music. He said he wanted to discuss plans for next season’s broadcasts, and he was short of time, so we talked while he got rid of his dress clothes and pink underwear. He then took a shower and dressed for travelling, conversing with me most of the time. (I think he wanted to make sure Philco’s sponsorship of the broadcasting would continue for the next season.) It was in the papers the next morning that Leopold Stokowski had rushed to New York after the concert and taken a ship to Europe.” [p.71]

When Philco made a broadcast demonstration at the Waldorf- Astoria Hotel in 1934, Alice got to sit next to Stokowski and wrote, “I was so impressed I am sure I had little to say.” [p.77] At the demonstration, Walter recalled “opera star Lucrezia Bori sang directly to the audience and then repeated the same numbers from a transparent, sound-proofed booth through a Philco high-fidelity receiver. The great applause of the audience indicated their approval of the comparative fidelity or naturalness of the program coming from the Philco receiver.” [p.73]

From “The Radio Weekly”, September 26, 1934

The high-fidelity demonstration was Walter’s professional swan song. Alice wrote in her chapter that by 1935 Walter’s health declined. After a second mastoid operation, Walter was “crippled and confined to bed with sciatica.” [p.78]

At the age of 51, Walter had to be pushed in a wheelchair between trains on a trip to see his adult daughter in Arizona. An ambulance carried him the last leg of his journey to the remote place where his daughter lived, Paul Spur, on the border with Mexico.

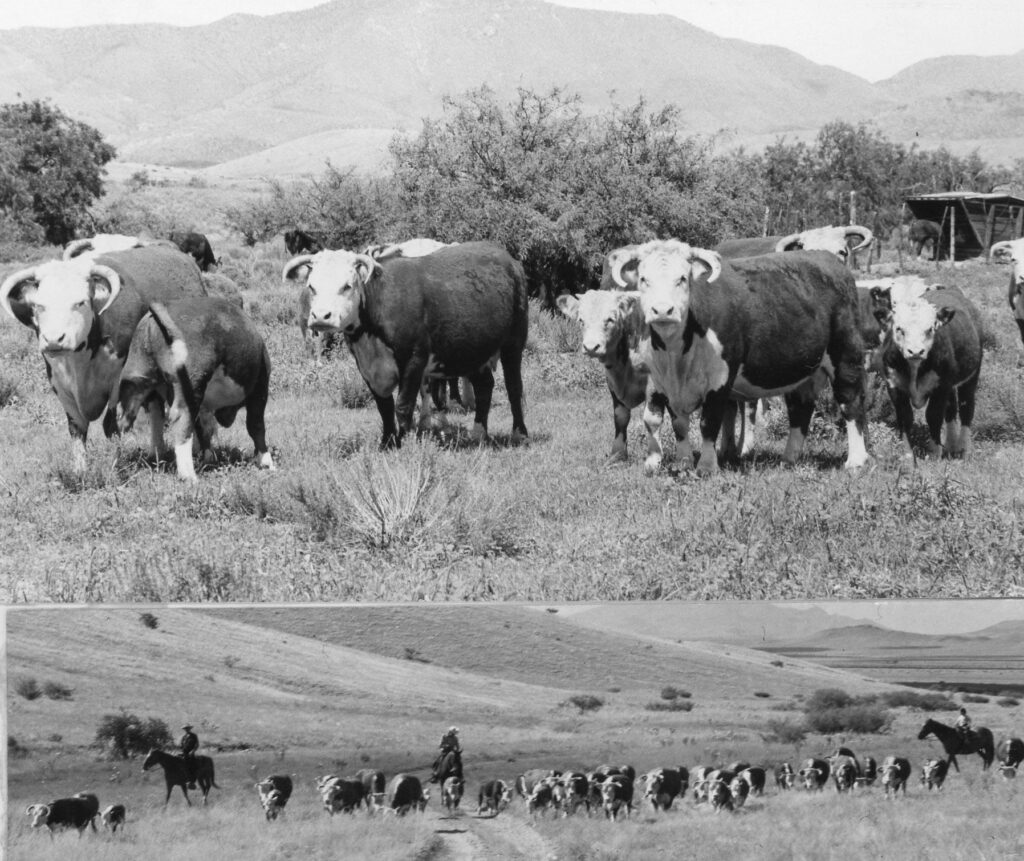

Surprisingly, Walter “responded to the warm sunshine and relaxation.” Just when I thought he hit the end of the road, Walter started his third career. He and Alice relocated to Arizona where Walter became a cattleman. He ran Rancho Sacatal, and “was twice elected president of the Arizona Hereford Association.” [p.79]

Cowboys herding cattle at Rancho Sacatal from The Arizona Memory Project

That’s where “Reflections” ends. Alice wrote, “You children know the rest of the story.” [p.79]

I don’t know the rest of the story that Alice referred to, only being a first cousin, 3 times removed. I have no connection to any of Walter’s descendents. I only have the book.

However, this is where stories are ultimately owned by the receiver. Regardless of what those reflections meant to Walter, Alice, their children and grandchildren, those reflections have given me perspective on my own struggles to balance work and family, ambition and love. And, thanks to Internet, I found the trail of Walter’s digital afterlife.

Reflections on Reflections

Nearly 60 years after self-publishing his story, Walter Holland still has a presence.

There are Philco magazine ads where he uses a phrase that needs to be resurrected, “false economy”. He’s mentioned in Philco radio history. There are historical accounts of his ranch. There are references to him in all kinds of Edison documents. And, there’s one particular photo.

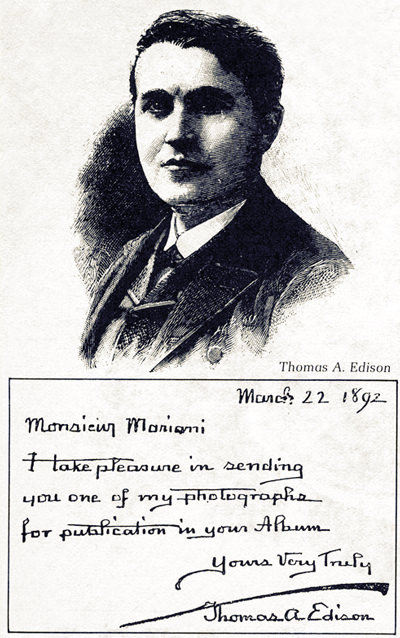

In 2011, a photo of Thomas Edison sold at auction for more than $31,000. In the picture, he cradles a large battery like a baby. He signed the photo, “I believe time will prove that the Alkaline Storage battery will produce important changes in our present transportation systems.” It had been property of Walter Holland.

Walter’s name is still linked with Edison and the battery. It feels like a legacy win to me. After all, Walter felt like he belonged to the battery. His nervous breakdown occurred about 18 months after this photo was signed.

One of Walter’s last correspondences with Edison was about the battery, after Walter had left the lab and was working in Detroit. Walter came up with an idea he thought could “make a considerable cost saving in the Edison battery.” He developed the idea and was issued a patent.

Edison lowballed Walter on buying the patent, offering $3000, “which was far below my estimate of one year’s cost savings. I should have known this was a good offer, as Mr. Edison seldom bought a patent … foolishly, I wrote that I thought that was not enough.” [p.46] Edison never replied. Walter was left with a worthless piece of paper.

For all his physical sacrifice, Walter’s work on the Edison battery and the electric car didn’t succeed. That is, it didn’t succeed at the time. A hundred years later, that electric car may finally catch on.

Perhaps some wizard creations just need more time to become a huge electric star.

All Quotes from “Reflections” (c)1965

By Alice and Walter Holland

Published by Palo Verde Press/Tuscon, Arizona