***

originally published September 23, 2014

***

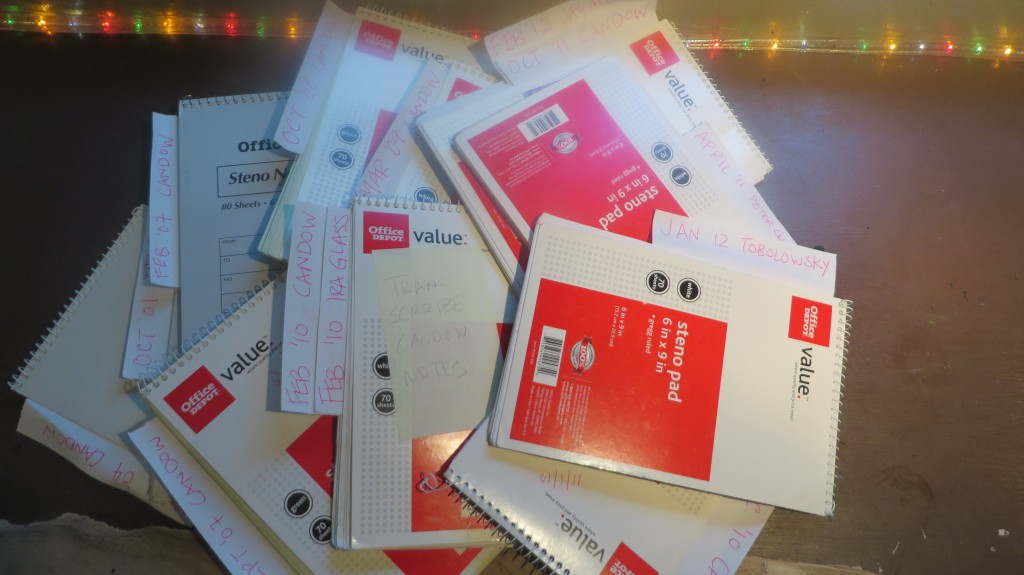

October 9th is the two year anniversary of the day I quit public radio. I wasn’t happy about walking away from a fifteen-year career in broadcast. It hurt to look at anything from my old job. I boxed up the eleven spiral-bound steno pads that hold more than a decade of to-do lists, pre-interview details, aircheck feedback, and notes from training sessions. I didn’t want to look at them again.

Last Thursday, though, I decided it was time to sift through the detritus of my years as a host, producer and editor. On top of the stack was a piece of paper, “Writing for Radio”. David Candow gave it to me during one of his annual training sessions at my station.

David was a former CBC producer and trainer who became a circuit riding consultant at public radio stations around the country. His list of yellow flags for writing hung by my computer for years. Looking at it last week, I thought, “I’ll never need this again.” I crumpled it up and threw it away.

The next day a friend who still works at my old station called me. She said, “Megan, I wanted to be sure you heard it from me. David Candow died.”

I sat in silence, which is rare for me. I started crying. David inspired me and encouraged me. His message about the power of oral storytelling made me feel like I belonged in public radio. Losing him severed the last emotional tie to my past life.

***

David started at the CBC back when the network still produced radio theatre. Like me, his first love was the stage and performance. Unlike me, he became a major documentary producer, a trainer for CBC Radio, and he traveled the world teaching journalism. I knew there would be tributes to him all over the place. He touched so many lives.

Right after I hung up the phone, and stopped crying, I started searching the Internet. I wanted to find something that went deeper than 140 characters, something to tell me what I didn’t know about him. I couldn’t find anything.

It wasn’t until late Saturday afternoon when I found Scott Simon’s remembrance on NPR’s Weekend Edition Saturday. I purposely avoided reading the transcript and listened to the audio instead. David Candow’s gospel was that the tone of your voice tells more than words on a page ever could. Voice conveys true emotion.

I was disappointed. Scott Simon used pretty words, but his script and delivery defied all of David’s teaching. It sounded like Scott was just reading the page, not speaking from the heart. He used the auto-voice of a seasoned broadcaster. With each sentence, I could hear David calling out, “Words don’t carry a message! Only TONE tells the listener what it means. Words by themselves mean nothing!”

Rather than a warm memory of a man who shaped a generation of public radio voices, I remembered what David Candow railed against in his trainings. I looked at the transcript of Scott’s commentary. It was exactly what he read on the air. To the eye, the tribute was fine. But, having spent days analyzing scripts with David Candow over my shoulder, prodding me to make it better, I saw yellow flags all over the place.

Since I already had the Pandora’s box of steno pads open, I took the time to go through each one and mark the pages of notes I made during David’s training. Then I transcribed the notes into a spreadsheet. It was something I meant to do since February 2010 – the post-it note reminding me to do it was still on top of the notebook. His words jumped off the page. I could hear his voice in my head again. And I saw exactly what David would say about his radio tribute, if he edited it.

***

Scott described David using adjectives. From a February 2010 training, I found this note:

“Bad Radio Habit #7: Using adjectives rather than verbs. Adjectives are paint by number. Verbs allow the listener to paint their own picture. Describing someone as a “plain woman with a brown sweater and simple shoes” tells me nothing about her as a person. Instead, recount the action of her character, “she would blush when spoken to and shuffle around the corner”.

Tubby reduces David to a caricature. David had the physique of a man who traveled thousands of miles of year, making his living on consulting fees. He didn’t think twice about eating tinned meat from a drugstore to save money. He built a house with his own hands. I never saw him sitting and relaxing.

“People who make their living on the air often distrust consultants.”

Scott assigned his attitude to all broadcasters. From a May 2004 training, I found this note:

“It’s wimpy to use “Those who say” or “Some people” or attribute statements to the masses. Stand up to being the devil’s advocate. Wear what you say as your own.”

When the Washington Post wrote an article about David Candow in 2008, they quoted Scott Simon. Candow led a training at my station six weeks after the story ran. He was humble about it, and laughed that Scott said anything. He said he spent very little time with him, and confirmed that Scott didn’t want to talk to him. David said their meeting had been years and years earlier, and that he didn’t hear that he made any difference in Scott’s delivery.

The yellow flags continue through the whole script.

A “good idea” from David’s “Writing for Radio”:

“The words which or that are strong indicators that you are about to write a subordinate clause. Put a full stop in front of them, and begin a new sentence.”

David’s advice came out of the knowledge that listening is linear and contextual. The ear can’t process information the same way the eye can. He would say, “the ear is lazy, the eye is greedy.” So, he advised us to only deliver one thought per sentence, in order, leading to a conclusion.

“The use of a conjunction in the middle of a sentence indicates you are linking two thoughts.”

The second reference to George Orwell, without telling me what George Orwell’s advice was. It reminded of something David said in May 2004,

“Don’t be stingy with knowledge. Don’t be exclusionary.”

I had to search online to find George Orwell’s Rules of Effective Writing to know what the comparison meant. I’ve read Orwell’s books, but I’m not an expert. As a listener, the reference made me feel like I didn’t do my homework rather than illustrating the subject of the tribute. I couldn’t remember what Scott said because I was too busy trying to figure out what he was saying.

Scott closed by saying,

If you’re reading this post rather than listening to the audio version, you’re missing my point. You’re also making it.

Radio is all about tone, something the written word can never provide. From May 2004,

“Tone is as important as script.”

It’s simply not compelling to hear someone read an article written for the eye.

In my indignation after hearing Scott, I e-mailed all my old radio friends, asking if they heard it. None of them did. They saw the written version, read it, and were touched by it. They even shared it on Facebook. Indeed, it’s a fine piece of writing for the eye. But, none of them listened to it.

In the era of the Internet, no one has time to listen. Not even radio professionals. Twitter was awash in mentions. I eventually found a tumblr site with heartfelt remembrances and personal photos that made me smile. A web producer shared an e-mail exchange about applying David’s work to the web – prophetic about the shift of media.

Lots of writing. No audio, except Scott Simon. It looked to me like David took radio – and the authentic tone of the human voice – with him.

***

Scott Simon flouted David Candow’s lessons, but he did me a favor. Had I heard a passionate, sincere and informative remembrance of the man who gave me my most valuable storytelling tools, I might not have gone back and combed through all those notes. David sprang to life again in my mind as I read them. My memories came back as vivid as when I struggled to make daily deadlines and produce radio that touched people’s lives.

Scott still has the deadlines. He still faces the pressures that I quit two years ago. He managed to turn around his piece and have it ready for national broadcast in twenty-four hours. It’s taken me four days to pull this together. I admit I’m not being fair in dissecting his work. We all express grief in different ways.

***

When David and I last met, back in October 2011, I asked him if he was archiving all his workshop information. He said he tried to write a book with his daughter. He said she’s an excellent writer. But, he found he couldn’t convey the importance of tone through writing.

David and I often talked about the tension between the oral tradition and the written tradition. The spoken word is transient and malleable while the written word is permanent and authoritative. He told me this as we discussed why it was so hard to get journalists to tear themselves away from the page, to let their natural way of speaking lead their delivery.

I grew up awash in oral storytelling. I admired Carl Kasell, Charlie Rose, David Brinkley, and Charles Kuralt – all fellow North Carolina natives. Their straightforward style and honest connection inspired me. David once asked me, “You know why so many radio people came from North Carolina?”

He said, like Newfoundland, it was a place of Irish immigrants and not much money. Oral tradition dominates where formal education is unavailable. As a result, the oral tradition was often connected with poverty and ignorance, people who didn’t have the benefit of learning from the higher form of the written word. But, David pointed out, radio is an oral medium.

I suggested recording a series of interviews where he could share all his experience and insight. Like music, you can’t learn radio from a book. David wasn’t interested. He was an itinerant preacher of a dying art form. I suspected he didn’t want to compete with himself. Maybe he wondered if anyone fly him in for a week of workshops if they could just buy a packet of audio files.

I don’t know the real reason he didn’t want to preserve his oral wisdom. But I do know I couldn’t cajole him into even one interview. When we parted I implored him to consider recording something. I hope he found a way to preserve the real magic of his teaching, if only the melody of his Newfoundland accent. I’ll keep listening for him.

***

I’m a story consultant and an independent producer now. Last week I threw away David’s “Writing for Radio” because I thought it no longer applied to me. But, that’s not the case. As I unearthed all my notes, I found that his teaching still applies.

So long as people talk to one another, mastering direct language and authentic tone pays off. Even if radio as an industry becomes simply a reading service for online articles, there will always be places where people want to hear humans sounding like humans.

You can’t replace sitting in a room with him, but for the sake of passing on the wisdom he gave me, I’ve created a spreadsheet of all my notes from Candow’s trainings, by date and topic. Feel free to explore it and see if any gems help you in your work.

I finally completed my post-it note task from 2010.

David Candow Notes, taken by Megan Sukys 2004-2011, documented 9/21/14

I also scanned pdf’s of all the handouts he gave me. He told me a producer helped him pull those together. He was reticent about documenting even that much. When he passed them out, he kept asking if they made sense, if they were helpful at all. They are. My thanks to the nameless producer who wrangled him into that much documentation.

Common Mistakes in Asking Questions