The worksheet asked third graders to determine whether creatures and characters were “real” or “fantasy”. My son made aggressive air quotes around the words as he told me about the assignment. His voice trembled with outrage, “There were pictures of dragons and fairies and unicorns and the whole thing was about how those things weren’t really real!”

The assignment was light-hearted busy work during his weekly academic enrichment class. It was supposed to fill time before lunch, but my son took it as a personal affront.

“I walked up to my teacher’s desk and told her I couldn’t do the worksheet because of my beliefs.”

I braced myself for the rest of his story, wondering if I would soon receive a call from his teacher. Growing up in a small Southern town, there was a distinct line between what was acceptable and what was devil worship. I learned early on to demarcate imagination from faith, never talking about my fascination with unicorns and magic in church or in school.

When I was in third grade, we had a special guest come into our class to tell us how to identify Satanists and to be aware how they were trying to snatch us from our loving families. It was 1982. Parents worried about the mental and moral damage caused by Ozzy Osbourne, Procter& Gamble and games like Dungeon & Dragons. This was the same year that the made-for-TV movie “Mazes and Monsters” aired. The boundary between reality and fantasy had to be firm, or else we would all end up trapped in our imaginary worlds, like poor Tom Hanks.

As careful as I had to be in public arenas, at home my mother welcomed conversations about the nature of reality. I could ask her all the questions that made my Sunday School teacher go pale. And if I came to the conclusion that I couldn’t accept something, she made it clear that I had to develop my own understanding of the world, that my faith could be my own.

My mother identified as a Christian without reservation, but she loved to probe the greater mysteries. She read Edgar Cayce. She talked about the possibility of multiple planes of existence, “A train could be rushing through this room right now in another dimension.” She would pose provocative questions.

In one Bible study she posited that Jesus was reincarnated, “The Bible says that Jesus knew what it was to be human in every way, but he didn’t do everything that humans do in his life. He didn’t kill, he didn’t steal, he didn’t marry. How could he know? What if,” she would get a twinkle in her eye when she asked ‘what if’, “What if Jesus lived before? What if Jesus had been Adam, Noah, Abraham, David? He would have had all those very human experiences, so when he came back as Savior, he could truly know what it meant to be human.” The members of her group shifted uncomfortably and let her question hang in the air without response. My mother told me about it with a sense of a humor, “I guess they hadn’t thought of that before.”

In 1984 “The Neverending Story” came out. My mom and I watched it together. We got it on Beta tape (my mother was insistent that Betamax was superior to VHS and that she would only get the best technology) and watched it over and over, especially the saddest part.

“It’s the Swamp of Despair!” She told me about “Pilgrim’s Progress”, the 17th century Christian allegory that included a swamp where the hero sinks under the weight of his fears and guilt – very similar to Atreyu’s horse Artax. She bought me my own copy of the book so we could discuss the significance of the image in relation to our real lives. “That’s what depression is, Megan. It will pull you under, but you have to have faith that you will be rescued, even when it all seems hopeless. That swamp isn’t reality, it’s not more powerful than God’s love.”

For years afterward, we would talk about our challenges in terms of the fantastic characters and situations of “The Neverending Story”, especially the idea that wishes, our hopes for the world, are the things that make that the future. All of my mother’s words carried more weight because she talked to me from her electric cart, unable to walk or work due to Multiple Sclerosis. She knew what it was to be immobilized, to lose the ability to meet the rest of the world, to feel stuck and alone due to circumstances beyond her control.

Reality for her was often full of pain and limitations, so she fiercely protected the freedom to think what she wanted, to believe in the ideas that kept her going through her own Swamp of Despair. Even though she couldn’t take me out to parks or on long trips, she helped me travel the galaxy and explore alternate dimensions through imagination. And she always made clear, “We don’t really know what’s real and what isn’t. With God, anything is possible.” It’s a gift I treasure, a lesson that shaped how I see the world.

Still, I struggled with my son’s vivid fantasy world. When he was in kindergarten, I’d interrupt his flights of fancy to make sure he wasn’t hallucinating or expecting an actual dragon to be hiding behind the tree. He’d look at me with disappointment and concern, “I know Mom. It’s IMAGINATION.” I can’t shake that early warning about Tom Hanks, I guess.

My instinct is to tell him to hide his “beliefs”, downplay its importance to him, couch it in terms that won’t upset people. I imagine the judgment of my upbringing and don’t want him to get labeled or outcast. Perhaps even more, I don’t want to be accused of being a bad mother. That’s why I’ve been trying to remember my own mother, to reach back to the years before she died, before she got so sick that even fantasy couldn’t break through the pain and disability. What would she say to my nine-year-old son?

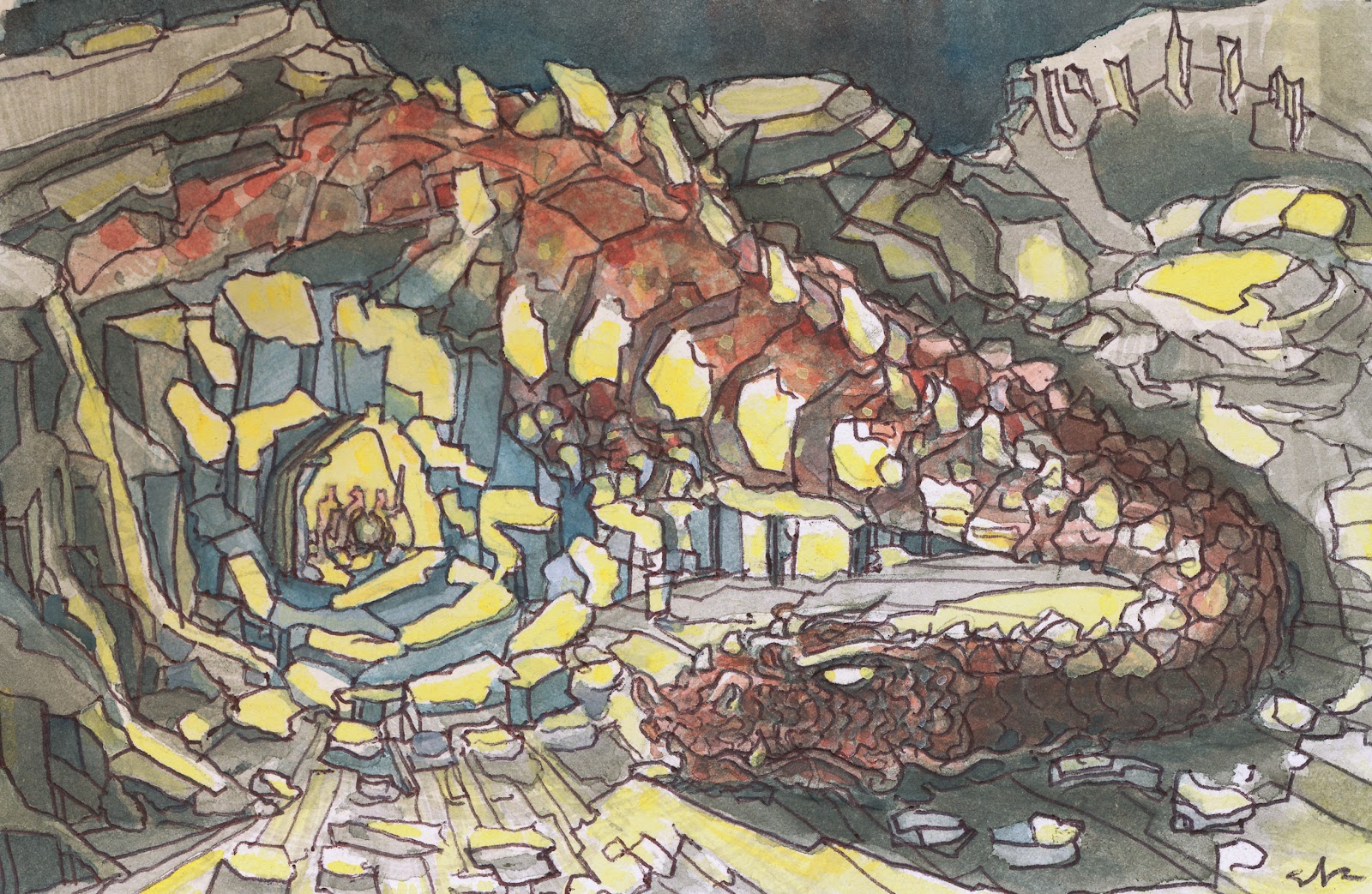

I didn’t take detailed notes of her words, I didn’t get a hard drive of her brain, I don’t yet have a phone that makes calls to the afterlife (iSeance, anyone?). If I want my son to learn from the woman who taught so much to me, to know her as more than just a picture in a frame, I have to conjure her from my memories. To have her wisdom and presence in the present, I can’t worry about what fits societal norms for “reality”. The only way to keep her real in my life is through fantasy.

When my son told me about protesting his assignment, he wasn’t looking for approval or advice. He felt confident about his actions, firm in standing up for his right to maintain his “beliefs”.

I tried to remain neutral, allowing the incident to be his own, “How did your teacher respond?”

He said, “She said she knows plenty of people who can see things that aren’t supposed to be real. She said she has friends who say they can see angels, and she believes them. Then she gave me a math problem that was so hard it took me till lunch to figure it out!”

That was it. He ran into the other room to play Minecraft. Even though I was prepared to tell him all about what my mother told me, he didn’t need it. He was fine in his “beliefs”. I was the one who was having a problem. I was the one who needed advice on how to handle being woo-woo without apology.

So I asked myself, “What would my mother say to me?”