My dad taught my Sunday School class for a brief time when I was fifteen. I wouldn’t have gone if he didn’t. He wouldn’t have gone if my mother didn’t make him.

He wasn’t the Bible study type; he was in alcohol recovery for the second time at the age of forty-five. Redemption was on the line.

The high school class never had many attendees. On the first day, when only two other students showed up, my dad took out his wallet and counted his cash. Then he pulled out his car keys and said, “How about a field trip?”

He drove us to McDonald’s. After we got pancakes and sandwiches, he sat down at the booth with a small black coffee and an aluminum ashtray. He lit a cigarette and admitted he didn’t know how to teach Sunday school. But, he knew the Bible was mostly stories to help you live your life. Since he couldn’t think of any Bible stories, he said he’d tell us a story from his life, from his days in the Navy.

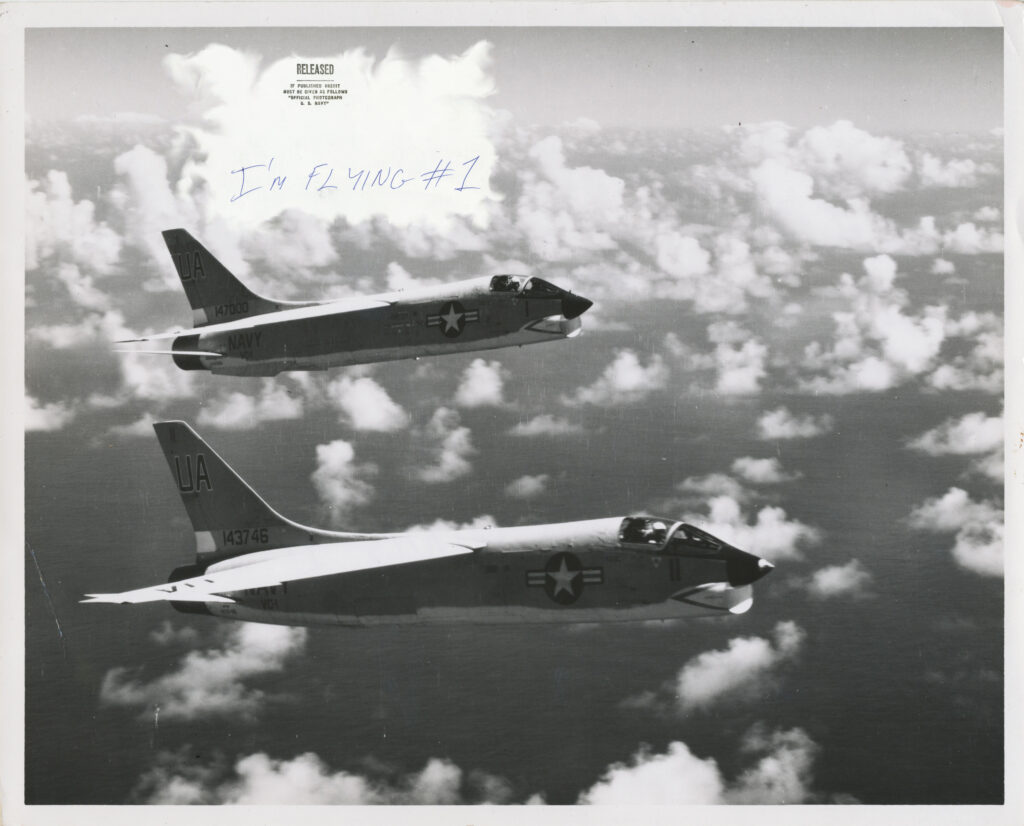

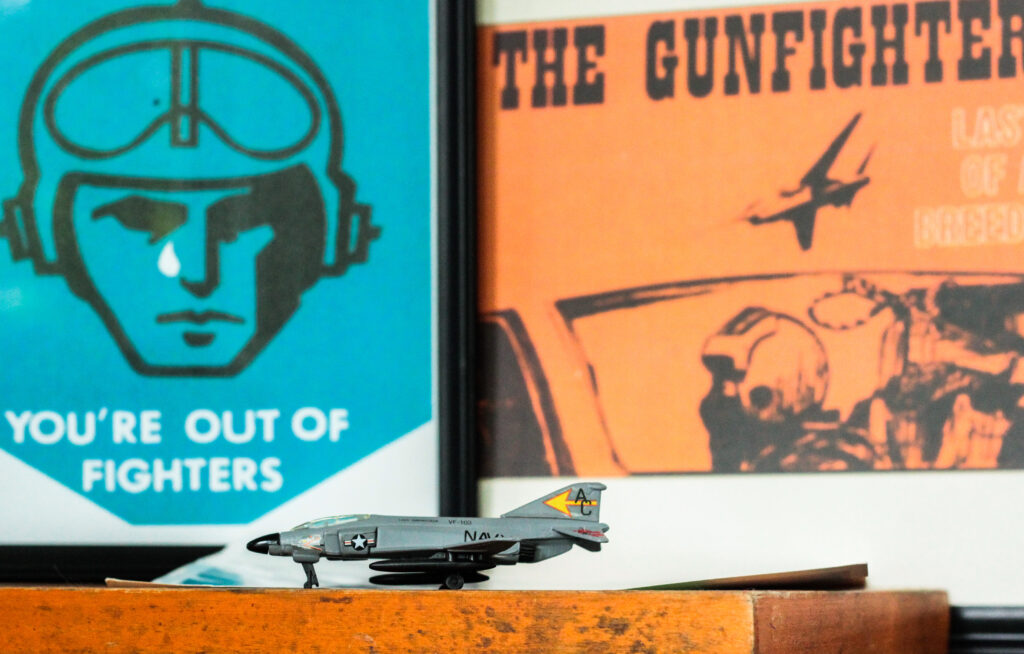

My dad never talked much about life in the military. He was a Navy fighter pilot stationed in Hawaii during the Vietnam War. That sentence pretty much summed up all he ever told me. His photos shared more words.

My dad would say “Fighter Pilot” like that was all I needed to know, like that title was beginning, middle, end. Before our McDonald’s breakfast, the closest he got to sharing Navy stories was when he tried to explain the flight simulator program on our new home computer.

I ate my Egg McMuffin, elbow to elbow with my fellow fast-food acolytes, while my Dad smoked and looked in the direction of the Mayor McCheese playground with a faraway gaze. He knew how to use the dramatic pause. I wondered which amazing adventure he was going to share.

Almost everything I knew about my dad I heard from my mom. My mother talked about his service more than he did. When he wasn’t around – which was most of the time – she told me how much he loved flying, to explain his manic depression.”Once you go supersonic, how is anything else in life going to match that?”

She told me how everyone in his squadron had alcohol problems, not just my dad. “Was it the men who became pilots or what being a pilot did to the men?” The planes he flew were notoriously difficult, earning the name “ensign killer”. My mom told me a friend of my dad’s was killed during take-off from a carrier’s flight deck – the jet just flew straight into the ocean.

My mother also told me my dad never seemed to recover from the trauma of his Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (S.E.R.E.) training. It was POW training, required of all pilots. She said he came back different, that the experiences left him shaken for years. The training is what he told us about in McDonald’s.

That Sunday, he was a long way from his high flying F-8 glory days. After three years sober, he fell off the wagon a couple weeks before my sister’s wedding. He lost his job at the car dealership. He had nothing better to do than accept my mother’s Sunday School enlistment.

The thrill and honor of his piloting was the farthest thing from his mind. Instead, he remembered the pain, the fear, all the things I never heard about from him. He said he had a hard time thinking of a story he could share with kids our age, but he thought he’d tell us a lesson that changed him during his service.

In one part of the training, my dad learned to find food in the wilderness. He told us how an officer held up a dove. My dad said it was the most beautiful bird, coo’ing softly as the officer pet its head. The officer talked about the importance of getting the most nutrition from every meal, that they should cook the whole bird body, no plucking or dressing. Then he ripped the bird’s head off and tossed the whole thing into a pot. My dad said that probably upset him more than anything that was to come.

Once they had their survival skills, his group was released in the woods and told to evade capture while crossing to a check point. He saw some soldiers just hide out, opting to wait till the training was over to emerge. Even though he tried to run, my dad said he got caught. His captors took him to a building where he was given a cigarette and a water. Then he was interrogated and a couple guys beat the mess out of him.

Once he was released into a cell, he found the other guys who hid out during the exercise. Evidently, they were picked up when the all-clear was given. Officers took them to a building where they were given cigarettes and water, then they were interrogated and got the mess beaten out of them.

He finally looked back at us Sunday Schoolers, across the pile of empty wrappers on the table. He said, “See? Either way, same ending. You can try to hide out, try to play it safe, but you don’t learn anything along the way. I mean, if you’re just gonna get a cigarette and a beating when it’s all over, why not try to get the most out of it you can before you get caught?”

Being only fifteen, I was still struggling to get past the dove decapitation, and the terror of imagining his training, and the brand-new awareness that my dad had an interior landscape totally foreign to me. I couldn’t begin to understand what his POW story meant to me, or even to him. I excused myself to get a refill of sweet tea.

My dad “taught” a couple more classes. Two more McDonald’s trips, but no stories. Just coffee and cigarettes and greasy biscuits. Then he told my mom he couldn’t do it anymore.

Soon after, he opened a consignment store. Then, he took up acting for the first time. My mom said it had always been a dream, but lifelong stage fright held him back. He decided he could finally face that fear.

I wish I could say that was the start of a whole new life, and a happy ending. It wasn’t. There were DUIs and mental commitments and the wild swinging of bipolar disorder still on his flight path. But, for a few more years, my dad got back into the pilot seat and took life for another spin.

Looking back, I could define my dad’s life by his failures, but I would only be cheating myself. I’m now older than my dad was in that McDonald’s, and I have debacles of my own.

I didn’t join the military, haven’t seen combat, I’ve avoided ever getting pummeled, and I can’t begin to understand the ways that his service during the Vietnam War affected his life. Despite his Sunday School lesson, I tried to play it safe, to hide out, to avoid getting caught. And I ended up having the proverbial mess beaten out of me all the same.

When I was fifteen, my dad’s advice to “get the most out of it you can before you get caught” seemed kind of obvious. (It’s easy to be smart before you actually learn anything.) I now see my dad’s advice is about having the courage to get back out there and play the game again. Even though you know exactly how much it’s gonna hurt at the end, and how little that affects the final outcome, you might squeeze a bit more learning out of life.

As resonant as his ‘get back out there’ message is, though, what means the most to me now is that when he was at his rock bottom it wasn’t old glories that got him through. It was the tough times. Remembering his POW lessons, that’s what gave him hope when his high flying days were over – not the promotional photographs.

That gives me hope because while I don’t have any dazzling achievements, I have plenty of painful lessons. Rather than letting those failures bury me, I might be able to use them – even if it’s just to pass on a little wisdom to kids who are still too young to use it.

**Historic photos are all official U.S. Navy prints**

**originally published May 25, 2015**