ART: Britton Sukys

I can’t stand losing. Especially when I think I’m in the right. Especially when I think my opponent is a monster. It’s enough to make me gnash my teeth, blow smoke out of my nose, and roar with fiery rage.

Eight years ago, though, I learned an ancient story that led me to reconsider my relationship with antagonists.

Back in the summer of 2016, on Washington State’s Peninsula, nestled deep in the Olympic National Park, the Sol Duc Hot Springs tempted me with warm waters and a fantastic origin story. An online blurb said:

Native American legend tells how the springs were created by dragons.

“Once there were two dragons. One lived in the Sol Duc Valley and the other lived in the Elwha Valley. Neither dragon knew of the other’s existence. One day they were both out exploring the forest when they came face to face on top of the ridge separating the Elwha and Sol Duc Valleys. They exploded with anger as each accused the other of invading its territory.

“The fight was brutal as the dragons thrashed and ripped at each other to win back their territory. After years of fighting and clawing at each other, they grew frustrated. Their strength was evenly matched and neither could win. The dragons both admitted defeat and crawled back to caves in their respective valleys and are still crying over being defeated. The dragons’ hot tears are the source of the hot springs in the Elwha and Sol Duc Valleys.”

I read this while my husband, my kids, and I were on a family vacation to the Hoh River Valley. I decided we had to take a day trip to Sol Duc. Dragons are kind of our thing.

During our first visit to the Hoh, we started playing Dungeons & Dragons as a family. The kids were four- and seven-years-old. Fantasy plays a central role in the way we talk about the world with our kids. I once suspected a dragon was responsible for a problem under our basement. My husband even summoned a dragon to watch over the alley retaining wall behind our house.

The thought of bathing in dragon tears was irresistible to my overactive imagination. With a legend like that, it had to be a magic place. Surely, the waters would grant me some powerful vision.

As we drove to the Sol Duc Resort, I imagined there would be dragon relics everywhere. In my mind, I saw myself discovering a portal to the primordial wisdom of the forest.

We paid the $25 entrance fee to the National Park and another $48 for day passes to the pools, and I mentally budgeted for the dragon T-shirts and traditional dragon art I was sure would be in the gift shop. I wanted to document whatever epiphany I received.

But when I got there, I found nothing about the legend. In fact, I couldn’t find any information on the local tribes. (I did find that lunch for four at the snack bar cost $78. Without any beer.)

Despite the lack of dragon souvenirs, historic documentation, or a frosty mug, the hot spring pools still enchanted me with their heat and lingering scent of rotten eggs. The forest hot springs are channeled into chlorinated, cement pools surrounded by a tall fence. The chlorine kills the germs, not the smell.

Soaking in the sulfur, I wondered about the deeper meaning of the legend. Stories, especially ancient myths, speak on many levels. Bathing in dragon tears, shed after bitter, endless battles, seemed like a powerful metaphor for dealing with an unwinnable feud.

It occurred to me that the steaming, stinky waters and their accompanying legend may have been a way to cook out the inevitable violent frustration that comes with uneasy truces. Drown your hot rage, sacrifice it to the fantastic beast that also couldn’t vanquish those deplorable neighbors.

After further poaching in the pools, though, I began to consider instead that the hot springs percolated warriors for another defense of sacred territory. Absorb the dragon’s rage and strength, fight for your terrible beast’s honor.

Depending on the day and situation, I could see either interpretation as good guidance. If I wanted to hard-boil my hunch, I’d need more context. I decided to track down the source story.

The National Parks Service manages the land where the dragon story is set. But the NPS didn’t have more information on their website.

I decided to check with the original storytellers. The tribes of the Olympic Peninsula include the Makah, Quileute, Hoh, Quinault, Jamestown S’Klallam, Port Gamble S’Klallam, Lower Elwha Klallam, Skokomish and Squaxin Island tribes. But back in the summer of 2016 I couldn’t find mention of the tale on any of the tribes’ websites.

In fact, the only online references to the legend were on tourist sites and they all circled back on themselves. There were plenty of dragon tears hits, but I couldn’t find which tribe first shared the story – or to whom.

Something smelled fishy. The purported legend started to reek of marketing gimmick. I knew better than to seek enlightenment from a clever commercial. I expected that further investigation into the Sol Duc dragon legend would reveal it as a modern fabrication. But, like all my other expectations, this turned out to be wrong.

I emailed the Olympic National Park, the Burke Museum, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, and the Quileute Nation. They were all incredibly helpful and generous.

I found that the story being used by the National Park was originally in the book “Gods & Goblins” by Smitty Parratt. Smitty grew up with a National Park Ranger for a father. Smitty went on to work with the National Park Service himself. The dragon legend was one of many stories he cataloged from the Olympic National Park. However, Smitty wasn’t a tribal source. He re-told the story as he heard it.

Then, a representative of the Quileute Nation helped put me in touch with Larry Burtness, the tribe’s grant writer and planner. He sent me this link to a Quileute account of the Sol Duc legend by Chris Morganroth III. There I found the same story of evenly matched opponents and hot tears, but the beasts were not called dragons, just monsters.

And then, Larry put me in touch with Jay Powell, an anthropologist who, along with his partner Vickie Jensen, has helped document many of the languages, stories, and traditions of Washington and British Columbia tribe. Jay sent me this account, as told by Hal George. Hal’s telling gave me a much richer description of the weeping creatures beneath the hot springs:

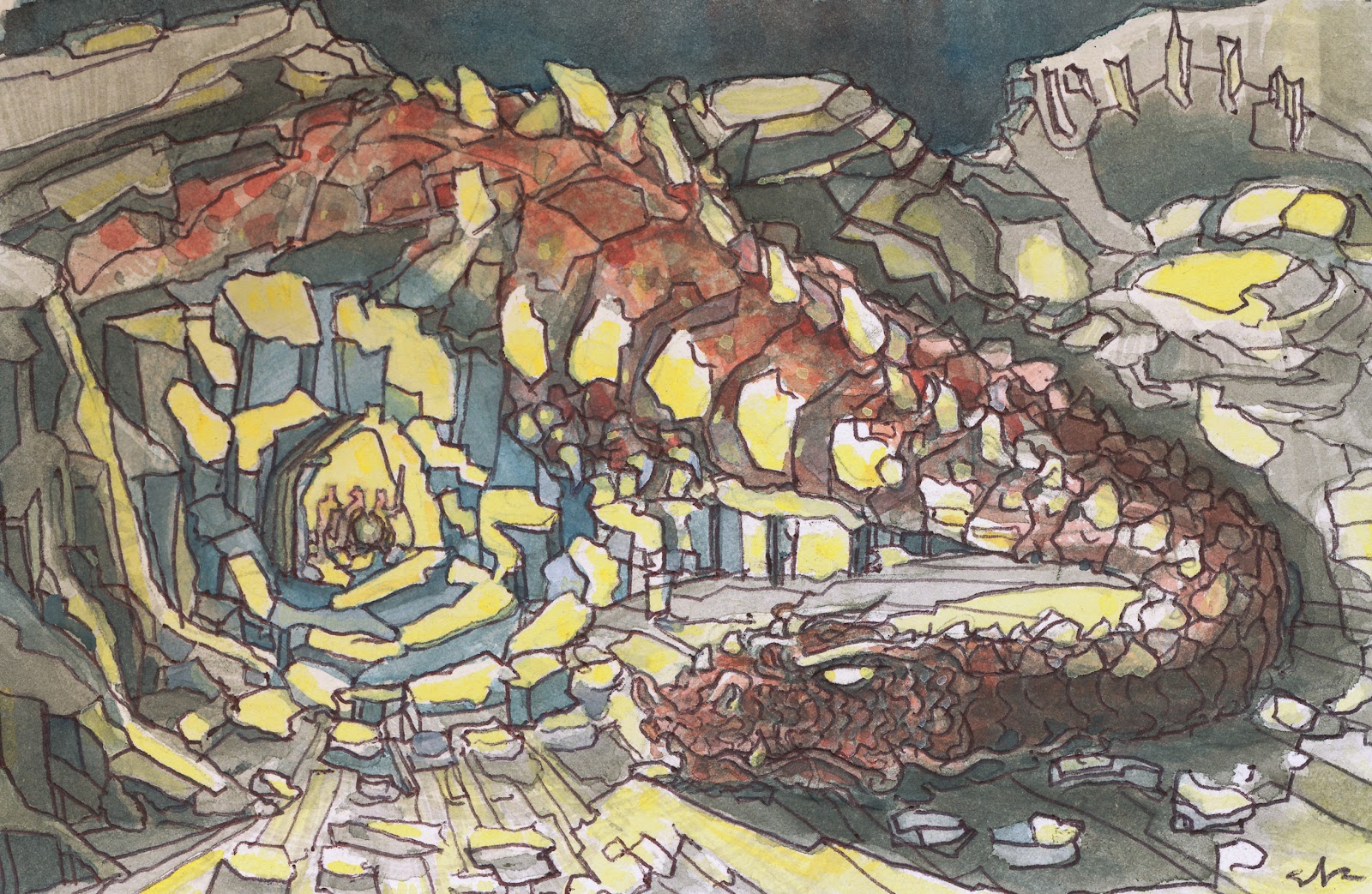

Both monsters were fierce, like martens, and strong and wiry and real smart because they were old. They had big mouths full of teeth as big as a man and sharp toenails. And their breath was like a hot wind that could burn you if you stood close, and they cooked their meat by just blowing on it. They were real big; when they walk through the woods you can see their heads and backs above the trees. When they fight they whip their tails on this side and on this (other) side and roll around. Their tails break off trees. And when they roll they flatten the trees they roll over. And sometimes the hard breathin’ sets the woods on fire around the battlefield. So that’s why nothin’ grows on Boulder Peak.

Well, then. Those two monsters are just covered with scars. They have scars all over their bodies from fightin’ because they have been meetin’ to fight for a lon’ time. They have big scars where their skin was ripped and tore. Every time they fight, they fight until they are bloody and tired, all bit, bones broke, skin ripped and burned. They have scars on top of scars.

But, they are even matched so one of them can never kill the other one. Neither one can kill the other one. We say they have ¶ibiti taxîlit, real stron’ spirit power. If you are a good warrior, you need that power. Neither one can kill the other. But they cause real bad injuries to each other every time they fight. Often them fights went on all day until night and it got dark. Then, they stop and roar. Both of them roar and roar and sing a victory song. The Quileute monster sang his song: “¶ip•ll• abi/ ¶ib•ti ti/l. ¶qpitilawli. Ahii. Ahiii. ‘A’a’aaaa. (four times) He’s talkin’ about havin’ a strong power and that’s why he is always winnin’. The Elwha monster sings, too. And then they roar some more and go home. They go to their cave.

These were my dragons! Mouths full of teeth, huge tails, breath to ignite the forest, and “real stron’ spirit power”. And there was the message to the warriors, “If you are a good warrior, you need that power.” Spirit power.

This documentation of the story is titled “The Border Monsters”. Jay Powell says that this tale takes place, “in the liminal region of peaks and rain-forest riverine headwaters where Elwha and Quileute territories come together”. The world liminal jumped out at me.

“Liminal” is used in anthropology, medicine, and literature. It refers to that confusing, slippery space of transformation between an old way and a new way. Terrible things can happen when we leave known territory and venture into wilderness. But, moving through that space is the only way to achieve lasting change.

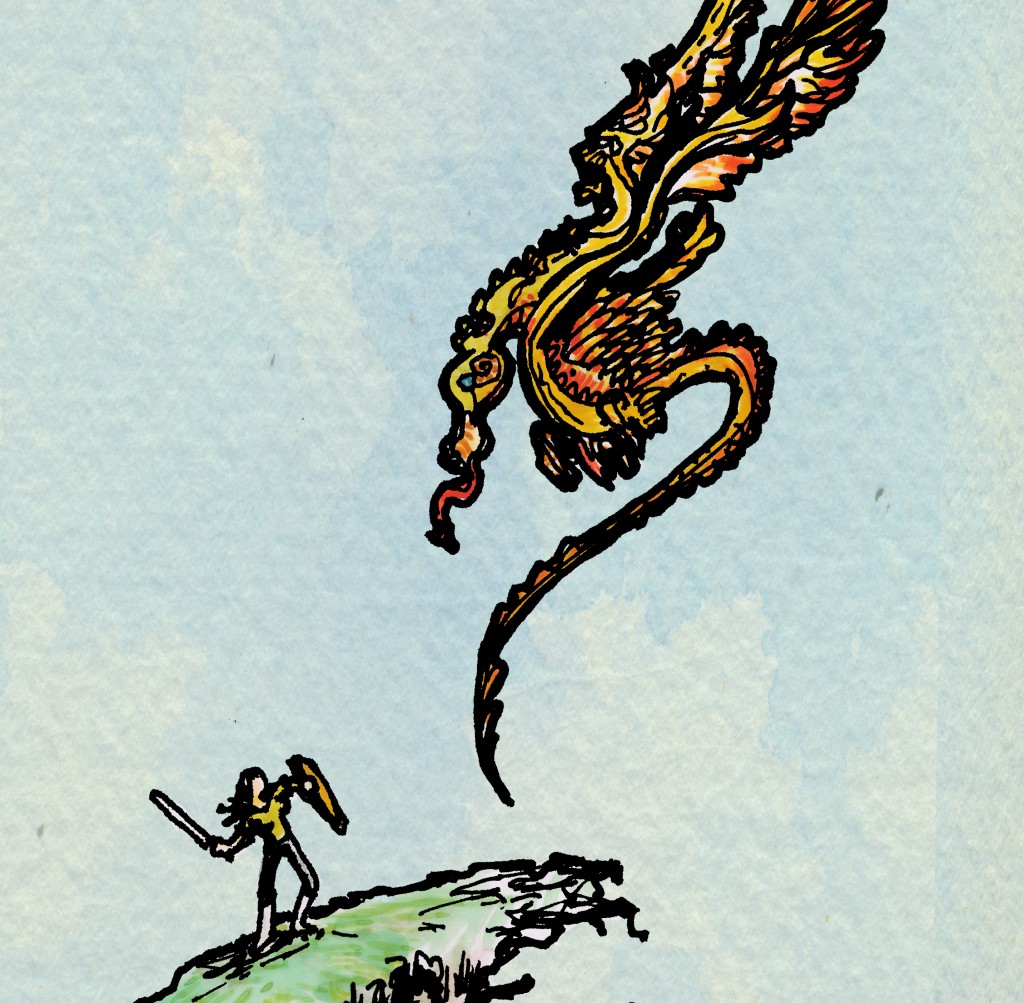

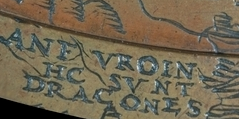

In the 16th century, liminal space on a map was noted with the phrase, “Here be dragons“. The idea of dragons as threshold guardians resonated. They have held that job in stories around the world. But border monsters didn’t set my imagination running. Soaking in their tears did.

I set up a makeshift hot spring in my tub at home, adding epsom salts, leaving out old eggs, and stewed on the matter. Wading deep into the realm of metaphor, I remembered that the phrase “take a bath” can also mean losing big on a major investment. Certainly, not being able to vanquish a perceived threat can feel like going broke.

In the Sol Duc legend as told by Hal George, though, “both of them roar and roar and sing a victory song”. The Quileute monster sings about having a strong power and, “that’s why he is always winnin’. The Elwha monster sings, too.”

It’s only once the monsters go home from the fruitless battle that they move a rock over their holes, lick their wounds, and cry. “They cry and cry because they are hurt bad.”

The description of the monsters sounded a lot like what I know as dragons, but the Quileute don’t use that word. According to Hal George, the Sol Duc dragon was named “the monster who cries in the woods”. It wasn’t named, “the monster who lost”, or even “the monster who sets the woods on fire”. The monster was known for the sorrow it felt that its perceived enemy was so evenly matched.

As preface to the Sol Duc legend, Hal George tells how the mythic Quileute hero Q’wati, called “The Transformer” in English, established the border between the Elwha and the Quileute. Q’wati piled up boulders at the boundary because the two tribes fought over territory “until Stormking Mountain had enough of it and tore off a big stone from his head. He threw it down and killed the warriors…” That’s how Lake Crescent came to be.

The dragons of the legend clash across a border meant to keep human battles from fracturing the earth itself.

Stories, especially ancient myths, speak on many levels. They also speak different lessons to each person, depending on what the person needs to know.

Hal George ends the story of the border monsters, “the monster who cries in the woods”, with “B8tsas sq’a. That’s what we say at the end of a story. B8tsas sq’a. That’s all there is to that.” This ending reminded me of many of the stories I heard from the older people as I grew up in small-town North Carolina. They often concluded, “And there you have it.” I take both of those sayings to mean, “And that’s just how it is.” The story isn’t a call to action, it’s a lesson to learn.

The Sol Duc legend taught me that if I want to break through the boundaries that fence me in, I will have to face a dragon at the divide. A dragon with an equal warrior spirit and conviction of righteousness. I cannot expect to defeat that dragon.

Unable to eliminate my foe, I can soak my head in the sorrow of my limitations. If I go too deep into those bitter tears, I could drown in despair. Or, I could steep myself for another painful, fruitless fight. Either way, those waters stink.

So what do I do when I find myself tore up and hurt real bad by the other side? I remember an important detail of the story, “one of them can never kill the other one.” Hal George makes that point two more times. “Neither one can kill the other one.” “Neither one can kill the other.”

I may never be rid of the people who believe and think and do things that are diametrically opposed to my existence. But they will also never be rid of me – or the many, many other people who believe and think and do things like me. Not winning isn’t the same as losing. Trying to vanquish the foe is an inffective strategy.

If defeat is impossible, another approach is to let my tears wash away my fiery rage, a rage so powerful it could burn up the very land that nurtures me. And once I’m drained back down to my human form, I can pack my real stron’ spirit power – rather than just teeth and nails and venom – to venture once more into the liminal space between my ideals and those of the opponent. That in-between is the place that promises true transformation.